When you ask someone who believes in such things why the Illuminati gives little clues —the pyramid on the back of the one dollar bill, the entire Denver Airport— about their world domination, they answer “they want to rub it in our faces.” Or something like that. The Powers that Be are so uncontested that they can just tell you what they’re doing to piss off anyone that’s Paying Attention. Very rude!

This is generally how I feel about property developers and their relationships to elected officials. In their influential 1987 book Urban Fortunes John R. Logan and Harvey Molotch argue that local elites disagree about a lot but all agree on one thing: growth is good. Grow the population, the size of the buildings, the amount of money in circulation— all of it. I’ve read Urban Fortunes probably four times now. I teach from it and reference it in my own book so it’s hard to miss examples of the growth machine in action.

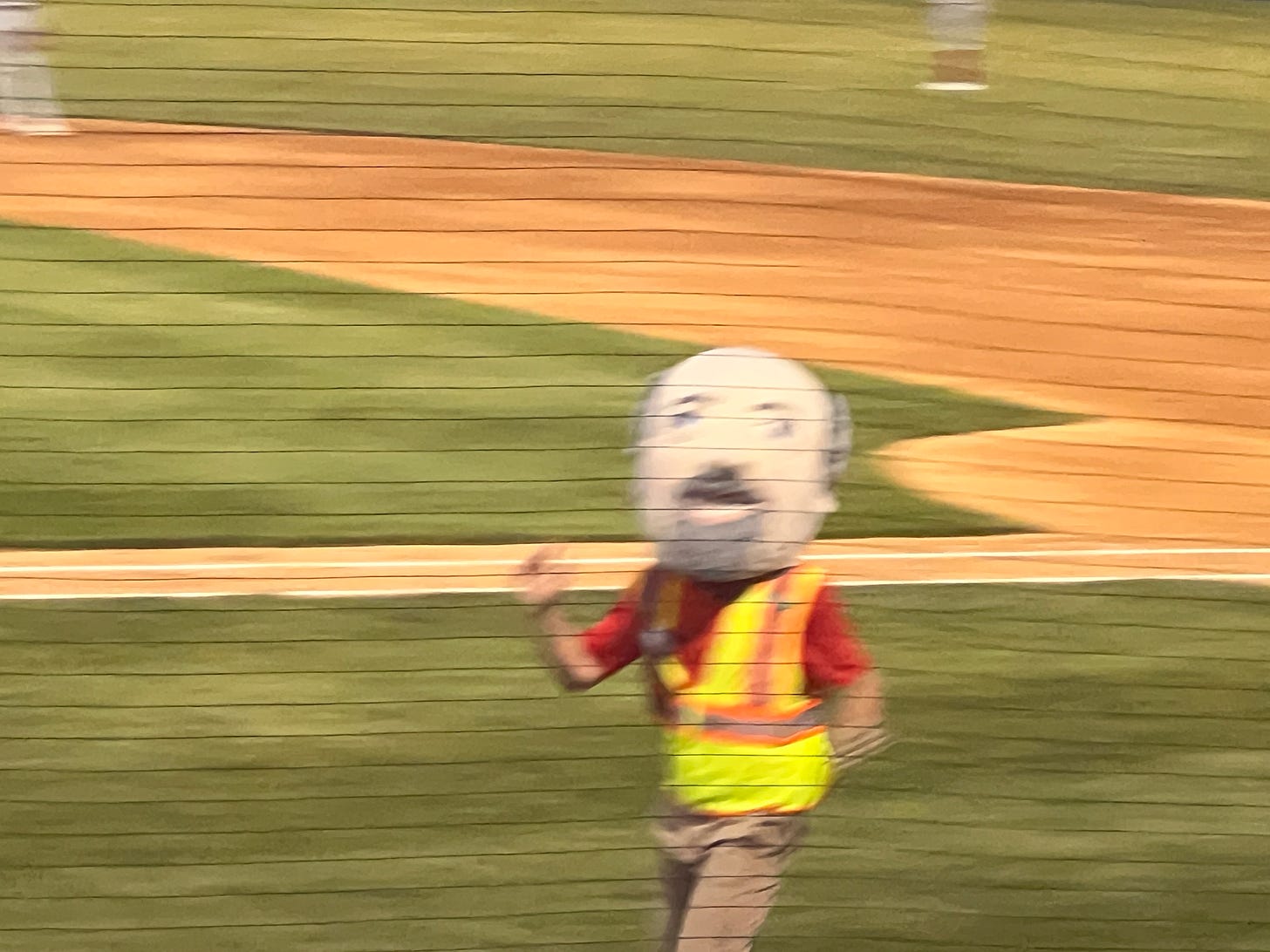

Every game of the Tri-City ValleyCats, usually somewhere between the fifth and seventh innings, is a “mayor’s race” sponsored by Rifenburg Construction. Employees that work at the ballpark don foam heads that resemble the mayors of Albany, Troy, and Schenectady and run a short footrace in which they cheat their way to the finish line. Sometimes one distracts the other two, maybe one shows up late but on a bicycle that lets them whiz past their competitors. It’s goofy fun and I deeply appreciate the implication that there is a storage room somewhere, akin to the Hall of Faces in Game of Thrones, where past mayors’ noggins sit in the dark collecting dust.

But honestly, when you step back and think about it, it is a bit tawdry that a construction company pays for a live comedy skit in front of thousands of people at a ballpark where mayors cheat and steal from each other in a literal race. They even wear high-vis vests and, before emerging on the field, are depicted on the big screen as having run off a construction site. It isn’t subtle, but it is also strangely difficult to find Rifenburg’s name attached to the ValleyCats online. Even this lengthly writeup of the mayors’ race doesn’t mention Rifenburg or any other sponsor.

The innocent, Occam’s razor explanation for not mentioning Rifenburg is simply that they don’t pay enough to be included in press and on the field during games. The sponsorship deal just isn’t that rich. And when you go look at Rifenburg’s headquarters just outside of Troy, it isn’t much more than a collection of humble warehouses off a country road. There’s no evil corporate tower in a far-away city. Just a family company that’s been around since 1958.

But that’s just the thing. When we think of the growth machine —or maybe it is more accurate to speak of hundreds, even thousands of growth machines in every city— we should think of these quaint relationships first and foremost. It is the deals, between local governments, small media markets, and regional construction contractors —or waste disposal companies, or agriculture, or a property developer, or or or— that make up what Patrick Wyman correctly identified as the American Gentry.

The gentry are “the salt-of-the-earth millionaires who see themselves as local leaders in business and politics, the unappreciated backbone of a once-great nation.” For Wyman it was the families that owned fruit orchards at the base of the Cascade mountains in Washington State. Here in upstate New York the same names that grace the century-old roads still sit on the boards of local non-profits, direct chambers of commerce, run for office and manage local businesses.

Americans like to think they live in a country with great social mobility and that the consequential class divisions are only detectable at the national scale. But that just isn’t true. Local government, and how it administers federal and state programs, has a much more consequential impact on your life than Congress, and when the World Economic Forum ranked countries on their new social mobility index the U.S. ranked 27th, behind many European nations and their former colonies like South Korea and Singapore.

It makes sense that our political efforts focus on the big fish —the multinational firms that drill for oil, bottle the water, and buy our homes— but so much of the world’s injustice is prosecuted by nobodies, running family firms, supporting their high school classmate’s run for city council. Truly lasting change begins with these relationships.