I haven’t had much to say lately but I’m going to try to change that by lightly editing something I’ve had on the back burner for awhile. This writing was originally part of my book The City Authentic but I had to cut it when I realized my word processor had been counting words inaccurately and I was well over my word count. I had then sought to submit it as a stand-alone essay in the New Left Review but they politely turned it down after some review. I still haven’t found a place for it so I figure this is where it belongs. I’ve broken it up into several parts like a TikTok video for engagement purposes. Haha jk it’s just really long. Hope you enjoy this thing I wrote the other day. -db

Following the release of his 1982 book All that is Solid Melts into Air, author Marshall Berman got into it with the editor of New Left Review, Perry Anderson. Anderson’s review of Berman’s book was incisive and Berman’s rebuttal (all published in NLR) had the disposition of “lol, okay stay mad.”

They are arguing over what “modernism” means. For Berman, there is “a dialectic of modernization and modernism”1 where modernism encompasses all the artistic, political and intellectual attempts at making sense of a rapidly modernizing world. To modernize means to retire the old relationships between people, land, and economy and make new ones that enable more production, bigger cities, and the creation of abstract wealth. The synthesis is the modernist: the kind of person that can “make their way through the maelstrom and make it their own.” All that is Solid Melts into Air, then, coaxes lessons on navigating modernism from the great works of literature and theory: Berman, through Baudelaire, Rousseau, Montesquieu, and –of course—Marx, sees meaning amongst the many disruptions wrought by capitalism. Revolution through these many sets of eyes is an ongoing, emergent phenomenon perpetuated by individuals’ artistic responses to a capitalist order. Berman’s hope is “that remembering the modernisms of the nineteenth century can give us the vision and courage to create the modernisms of the twenty-first.”2

Anderson counters: Berman’s modernism “is the emptiest of cultural categories.”3 (Ouch!) It lacks —as any Marxist would expect— material grounding. A more accurate treatment of the topic would be a “conjunctural explanation”4 (emphasis Anderson’s) that triangulates across three coordinates: the control of the arts and cultural artifacts by a dying aristocracy; the emergence of the technologies of the second industrial revolution (e.g. the telephone, automobiles, radio and so on); and the “imaginative proximity of social revolution.”5 The intersection of these three coordinates is modernism and it died just after World War II. Optimism for worldwide fraternity and solidarity, the end of hunger and want, were dashed not by war but by the peace. Anderson writes,

the old semi-aristocratic or agrarian order and its appurtenances was finished, in every country. Bourgeois democracy was finally universalized. With that, certain critical links with a pre-capitalist past were snapped. At the same time, Fordism arrived in force. Mass production and consumption transformed the West European economies along North American lines. There could no longer be the smallest doubt as to what kind of society this technology would consolidate: an oppressively stable, monolithically industrial, capitalist civilization was now in place.6

All that is Solid, according to Anderson, is a dangerously unserious book that has confused modernism and revolution to such a degree that each “dwindles to mere metaphor.”7 For Anderson, modernism was squashed decades ago, for Berman the continued existence of capitalism’s modernizing forces means that, definitionally, modernism still exist so that modernists can make sense of the modernizing forces around them.

Every day I wake up is another day further away from Berman and towards Anderson. I have to admit that I’ve loved Berman for a long time— I’ve even submitted (and thankfully had turned down) essays calling for a new “marxist humanism” to pick up where the Great Modernist Mensch left off. But even as I see Berman’s work in everything, I find myself drifting —marching?— ever closer to Anderson.

There’s a part in Berman’s rebuttal where he lists little things he sees every day —Mothers and daughters arguing on the bus, a peak at Carolee Schneemann’s Domestic Souvenirs— to demonstrate that modernism is still alive and well and that Anderson sees sour weeds where dandelion’s bloom. It’s at this moment in the text that I remember a bitter-sweet scene from the depths of the pandemic. A student, bright and inquisitive, suddenly disappears from my class. Her absence lingers enough that I set up a Zoom call and we talk about depression, anxiety, and the end of the world. I show her my own prescription bottle for 20mg Citalopram and for a moment we are sharing a lifeboat lashed together with pharmaceuticals and broadband. Just a brief moment where two modernists are making do in a constantly changing system.

But that’s just survival. It isn’t a political program for liberation, and while commiseration and empathy are essential to what it means to be social, they do not constitute a culture. Ultimately, this is what Berman and Anderson are arguing about. More than semantics, the definition of modernism is the keystone to a liberated culture. It is the goal, the aspiration, the vision of what the left is building over successive generations.

What would a genuinely new culture for the left look like? For Anderson,

a genuine socialist culture would be one which did not insatiably seek the new, defined simply as what comes later, itself to be rapidly consigned to the detritus of the old, but rather one which multiplied the different, in a far greater variety of concurrent styles and practices than had ever existed before: a diversity founded on the far greater plurality and complexity of possible ways of living that any free community of equals, no longer divided by class, race or gender, would create.8

Berman is characteristically coy in his own concluding vision, saying that,

We can contribute visions and ideas that will give people a shock of recognition, recognition of themselves and each other, that will bring their lives together. That is what we can do for solidarity and class-consciousness. But we can’t do it, we can’t generate ideas that will bind people’s lives together, if we lose contact with what those lives are like. Unless we know how to recognize people, as they look and feel and experience the world, we’ll never be able to help them recognize themselves or change the world.9

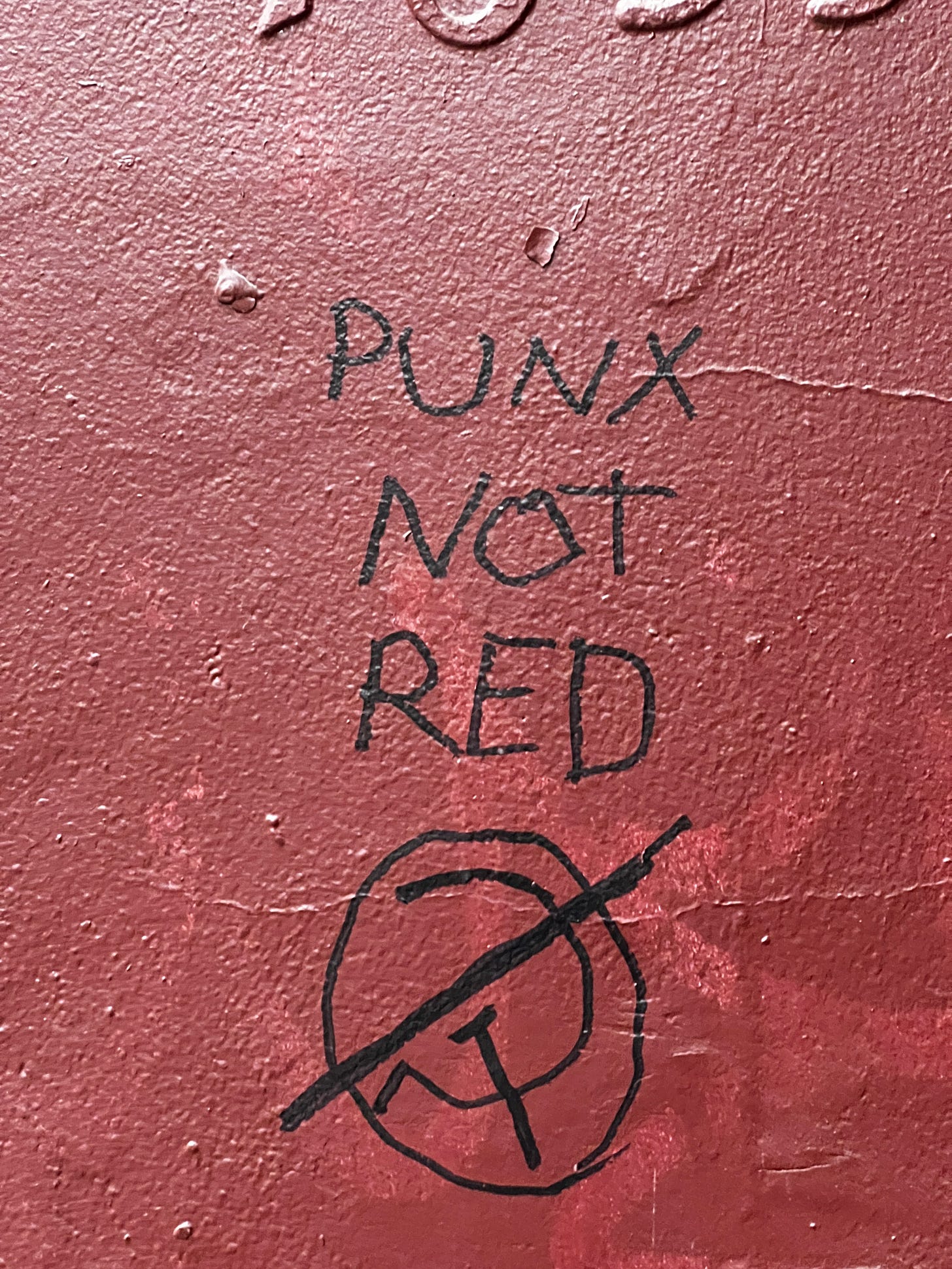

Now here we are, nearly a quarter of the way into the twenty-first century, and while the North American left is resurgent, it is still very weak and bears little resemblance to either Anderson’s infinite diversity and complexity in the face of oppressive stability or Berman’s continuous shocks of recognition that are meant to lift us out of the kaleidoscopic barrage of capitalist dynamism. Instead, the young 21st century is best captured by one of its early victims: the late Mark Fisher. For Fisher, the left has turned into a vampire castle10: a backbiting trap of snobbery and condescension that produces guilt and fine-grained identities from which individuals can lob accusations of inauthenticity and privilege. Attempts to escape the vampire castle and capitalist consumer culture are “precorporated”11 into just another subculture to consume in the marketplace.

My aim with this series is two-fold. First, I want to revisit this debate between Anderson and Berman over “a genuine socialist culture” with a particular focus on the role of identity formation and the notion of “being authentic” as Berman describes it in his work. While I do not believe that Berman’s marxist humanism needs to be resurrected, its central question regarding the balancing of individual human flourishing and collective material needs is an important one. Indeed, Anderson, before laying out a forceful critique, acknowledges that All that is Solid Melts into Air, “deserves the widest discussion and scrutiny on the Left”12 which is a nice way of calling for a dogpile.

In part 2 I will provide a brief overview of the underlying theory that drives this issue of balancing flourishing with the allocation of scarce resources. Again, Berman asks the right questions, even if his answers are flawed. If we are to take a conjunctural approach to the contemporary moment as Anderson prescribes, we will see that the historical contingencies and material realities of twenty-first century activism can give us new answers to the humanists’ old questions. In part 3 I will update Berman’s work for the social media age by reading the documentary This is Paris (2020) through Berman’s analysis. By looking at Paris Hilton, the tortured capitalist, we can also reckon with the parts of her that have been exported into our own lives.

My second aim is to reignite speculation around what “a genuine socialist culture” would look like. Of particular concern is the issue precorporation. I suggest that our social media-driven culture now invites us to defang the power of subcultural resistance ourselves, rather than wait for corporate trend spotters to find and precorporate that which we find meaningful. I call this process autocorporation. By way of conclusion, I will argue that the way out of autocorporation is comradely discipline as Jodi Dean defines it- as one side of a coin which, on the obverse contains joy. Together they are the “two aspects of comradeship as a mode of political belonging.”13 Put simply, Dean gives us insight into the sort of culture that would cut through the layers of cynicism and irony that American leftists have built up as both psychic and rhetorical shields from years of failure, infighting, and trauma. Between Fisher and Dean’s work it is possible to imagine a socialist culture that avoids autocorporation and lets us earnestly fight together. Such a world would dispense with a search for authentic expression of individuality and instead find comfort in discipline and purpose in collective action.

Perry Anderson, “Modernity and Revolution,” 1984, 112.

Marshall Berman, “The Signs in the Street: A Response to Perry Anderson,” 1984, 115.

ibid, 36.

Anderson, “Modernity and Revolution,” 112.

ibid, 104.

Berman, “The Signs in the Street: A Response to Perry Anderson,” 104.

Anderson, “Modernity and Revolution,” 106.

ibid, 113.

Berman, “The Signs in the Street: A Response to Perry Anderson,” 123

Mark Fischer, “Exiting the Vampire Castle,” OpenDemocracy, November 24, 2013, https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/opendemocracyuk/exiting-vampire-castle/. And yes, you’re probably tired of hearing people cite this essay but let me take my shot at it.

Mark Fisher, Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative?, Zero Books (Winchester: O Books, 2009), 9.

Anderson, “Modernity and Revolution,” 100.

Jodi Dean, Comrade: An Essay on Political Belonging (London ; New York: Verso, 2019), 10.