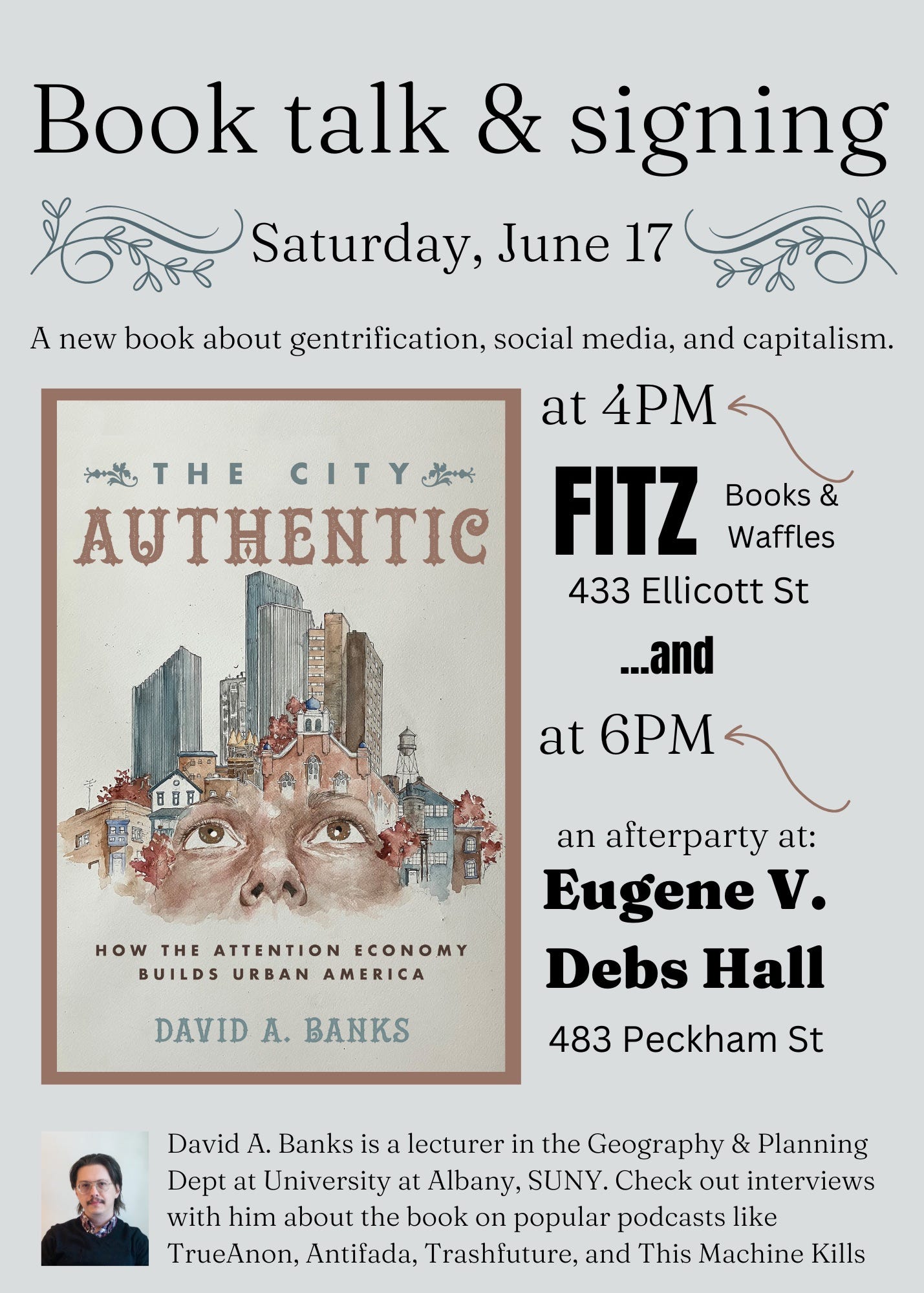

If you’re in Buffalo come out to my next book signing on June 17! More details at the bottom.

The right to the city is a very old idea expressed in many different words but its current instantiation is derived from Henri Lefebvre’s 1968 Le Droit à la ville. In this short book Lefebvre gives a whirlwind history of cities, describes their underlying class character, and the emerging scientific management of the city. The gist of Lefebvre’s argument is that cities used to be “the act and oeuvre of a complex thought” – a place where humanity expressed itself in an accumulation of culture, social action, and labor. But with industrialization and commodification came a stultifying conformity brought on by a series of crises and subsequent capitalist reactions. The accumulations of art and culture were becoming factories of trinkets and spectacles.

To overcome this plight people must come together to reassert democratic control over not just the city, but the society and culture that is endemic to it. The right to the city then, is something exercised in collaboration with others—never individually—and always oriented toward the future. The city isn’t a tourist trap to visit, it is the engine of society itself and if it isn’t maintained by the people in a participatory manner, then it will produce nothing but a stultifying, cartoonish facsimile of its least objectionable parts. A landscape of Whole Foods, Bank of America branches, and restaurants with names like Twig & Cartlidge.

But we shouldn’t leave the right to the city in the hands of Lefebvre. For all he contributed, he has an awful set of opinions about sexuality and gender and so his conceptualization of who the city is for and how we gain rights to its future are going to be hemmed in by a lack of imagination around life courses and experiences.1 Instead let’s leave the right to the city in the collective hands of the Brazilians that drafted the City Statute or Law No 10.257 of 2001.

The City Statute, an amendment to Brazil’s 1988 constitution, enshrines into law the social functions of property and land. An American could perhaps understanding it easier as the opposite of our own constitution’s fifth Amendment. Rather than uphold private ownership as the essential right that even the government itself must respect, the City Statute emphasizes democratic management and collective interest. A series of commentaries on the City Statue is both more readable and directly applicable than anything Lefebvre ever put to paper.

Keeping with this comparison of right to the city versus right to private property- few would argue that these rights are unevenly exercised and distributed. Some (children, the mentally incapacitated, and for a long time women and anyone that wasn’t White) did not have Fifth Amendment rights. But today it is more accurate to say that by law, nearly everyone has some form of property rights but few opportunities to exercise them. Few can afford property and even fewer could afford to defend it from the banks, insurance companies, police departments, and increasingly more frequent acts of god that threaten our material possessions. The laws are too complicated, the lawyers are too expensive, and the adversaries are too powerful. We have rights to property but few ways to actually and fully exercise them.

Can we say the same for collectives and their right to the city? Are there certain kinds of organizations and political formations that are better or more readily welcomed to exercise their right to the city than others? I would say the answer is undeniably yes. We could go even further and say that those organizations that can effectively exercise the right to the city are those that have enough discipline among their ranks to see a project to its conclusion. Because while money does as its told –it pays for the policeman’s baton, the lawyer’s briefcase, and the influencer’s smile– people must be organized and disciplined to act in unison.

What the commentaries on the City Statute make clear is that creating a legal requirement for participatory city planning (among other legal benefits) was just the beginning. Then came the fight to not only be heard, but to organize into a single voice to be obeyed. The City Statute set up the board, but you still have to play the game. Capitalist developers working in their private firms already understand the planning process and can utilize their hierarchical, nondemocratic firms to act quickly, decisively, and effectively to build condos-over-banks and smoothie shops. The people have to be organized, educated, and deployed to compete. Someone from the favela may understand their plight acutely, but if they are not enrolled in a group that also understands the political system just as well as the developers, they will never realize their full right to the city.

This is all necessary preamble to what otherwise would have been a startlingly aggressive statement: rights are as good as your discipline to secure them. This cold, decidedly unchill word –discipline– is the key to success in mass movement politics. “Discipline and joy” writes Jodi Dean in Comrade, “are two sides of the same coin, two aspects of comradeship as a mode of political belonging.” It isn’t enough to be the victim of the same forces, survive the same tragedies, or share an identity. One must consistently hold themselves to account for a shared political struggle.

You don’t need to be in a guerrilla training camp to recognize the need for, and the benefits of, discipline among a dedicated group. A local election, a bake sale, hell even planning a party can all go achieve their greatest successes when the group taking them on practices discipline. That means showing up to meetings on time, executing the tasks you’ve taken on, and holding others to account. That last one seems particularly hard for leftists because of the rebelliousness inherent in the ideology. We all had to recognize the illegitimacy of an authority to think about the world the way that we do, but that does not mean purging all forms of authority from our lives. Legitimate authority comes from a group you are accountable to and having done so I can certainly agree that with that discipline comes they joy of collective success. It feels wonderful.

I respect my readers too much to offer self-help advice and encouraging discipline is anything but self-help. It is the establishment of community support. The imposition of discipline is a brace, not a cudgel, for community life. “Discipline—meetings, reports, work, demonstrations, campaigns, “unity of action,” carrying out the line—provides the language through which previously inchoate and individual longing becomes collective will.” Dean writes earlier in Comrade that, “discipline of common struggle expands possibilities for action and intensifies the sense of its necessity.” If there’s any sort of intervention we need right now it is one that helps us filter out the growing spectacles in our cities, focus on the necessary, and expand what is possible.

In case you’re in Buffalo:

Something I’m listening to right now: